Frequently Asked Questions

What is bioethics?

Bioethics is defined by the American Society of Bioethics and Humanities as “the subfield of ethics that concerns the ethical issues arising in medicine and from advances in biological science.”1

A longer definition takes into account the history of bioethics and its expansion over several decades into multiple fields of inquiry and practice beyond that of its origins in medicine and healthcare. Ethics is a philosophical discipline pertaining to notions of good and bad, right and wrong—our moral life in community. Bioethics is the application of ethics to the field of medicine and healthcare, yes, but also population and public health, ecological and environmental concerns, issues arising from artificial or augmented intelligence, and much more.

Ethicists and bioethicists ask relevant questions more than provide sure and certain answers. What is the right thing to do and the good way to be? What is worthwhile? What are our obligations to one another? Who is responsible, to whom and for what? What is the fitting response to this moral dilemma given the context in which it arises? On what moral grounds are such claims made?

Bioethicists ask these questions in the contexts of modernity. They draw on a pluralistic plethora of traditions, both secular and religious, to spawn civil discourse on contentious issues of moral difference and others on which most people agree. Bioethicists foster public knowledge and comprehension both of moral philosophy and scientific advances. They note how biomedical technology can change the way we experience the meaning of health and illness and, ultimately, the way we live and die.

Bioethics is multidisciplinary. It blends such disciplines as philosophy, history, sociology, anthropology, literature, law, theology and religious studies with medicine, nursing, population health, and the medical humanities. Insights from various disciplines are brought to bear on the complex interaction of human life, science, and technology. Although its questions are as old as humankind, the origins of bioethics as a field are more recent and difficult to capture in a single view.

When the term “bioethics” was first coined in 1971 (some say by University of Wisconsin professor Van Rensselaer Potter; others, by fellows of the Kennedy Institute in Washington, D.C.), it may have signified merely the combination of biology and bioscience with humanistic knowledge. However, the field of bioethics now encompasses a full range of concerns, from difficult private decisions made in clinical settings to a variety of other concerns: aging and end of life, controversies about abortion and assisted reproductive technologies, broader concerns such as international human subjects research, the democratization of research, public policy and population health, vaccination mandates, and the allocation of scarce resources in times of pandemic. This array of interests is neatly summarized under the rubric of the Center for Practical Bioethics’ six program areas: Advance Care Planning, Community Education and Engagement, Professional Education and Clinical Services, Policy and Personal Guidance, Technology and Science, and Population Health.

As bioethics continues to evolve, it has become a prominent force in legislation and public policy, and in other practical applications of theoretical principles. Over the decades, the Center for Practical Bioethics has initiated and collaborated with partners on projects with names like the Ethics Committee Consortium, Ethics Roundtable, Compassionate Caregiver Rounds, Compassion Sabbath, Caring Conversations, Community-State Partnerships to Improve End-of-Life Care, Sabbaths of Hope, the PAINS Project, PAINS-KC, Transportable Physicians Orders for Patients Preferences (TPOPP), Coalition to Transform Advance Care (C-TAC), KC-4-Aging, MetroCARE, Kansas City Medical Society Foundation, Ethical AI Initiative, COVID Ethics Update, and more.

Some would argue that what began as a multi-disciplinary field of study is now a full-fledged discipline in its own right. Bioethics has a burgeoning literature, with journals and publishers. There are hundreds of vocational specialists in clinical ethics consultation, and others in bioethics departments within traditional academia. There now are many programs of training and education, ranging from Bioethics Certificates to Masters and Doctoral degrees in Bioethics. There are guilds and societies for bioethicists, the largest being the American Society of Bioethics and Humanities. ASBH has implemented a certification exam for healthcare ethics consultants and has published a code of ethics as well.

After a few decades since its conception, Bioethics indeed has grown up.

Tarris Rosell, PhD, DMin, HEC-C

01/28/2023

1 Chadwick, R. Felicity (2019, May 27). bioethics. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/bioethics

What is ethics consultation?

“A set of services provided by an individual or group in response to questions from patients, families, surrogates, healthcare professionals, or other involved parties who seek to resolve uncertainty or conflict regarding value-laden concerns that emerge in health care.” (American Society for Bioethics and Humanities. (2011). Core Competencies for Healthcare Ethics Consultation (2nd ed.). Glenview, IL: Author)

Ethics consultation regularly takes place in hospital settings where it may be referred to as clinical ethics consultation.

A houseless patient arrives with frostbite and subsequent necrosis of both feet. She cannot identify any friends or family surrogate decision-makers but is assessed to lack capacity for major healthcare decisions. Her injuries are so serious as to require bilateral amputation, a life-saving intervention that the patient declines on grounds that her feet have computer chips implanted to self-heal. The hospitalist attending physician asks his Ethics colleague, “What do we do now? Should we amputate or not?”

Oftentimes ethics consultation to the Center for Practical Bioethics comes by way of a phone call or email query from someone who could be located anywhere.

My mother is in her late-80s with some dementia. I am needing to make more of her healthcare decisions, but she never signed a document making me her legal power of attorney. Is it okay if I have her sign this form I found on your website?

Sometimes it is a public policy matter that is morally perplexing to someone who has to make decisions that impact a lot of other people. Ethics consultation could be helpful for a state legislator who is unsure about specific terminology used in the draft of a proposed bill pertaining to women’s reproductive rights and termination of a pregnancy (abortion). Ethics consultants at the Center for Practical Bioethics have responded to requests of this sort and others many times, and will continue to do so when consulted for ethics help.

Tarris Rosell, PhD, DMin, HEC-C

02/06/2023

What is a healthcare ethics consultant?

A healthcare ethics consultant (HEC) is “a professional in a healthcare setting who seeks to identify and support the appropriate decision maker(s) in a given situation involving ethical questions and to promote ethically sound decision making by facilitating communication among key stakeholders, fostering understanding, clarifying and analyzing ethical issues, and including justifications when recommendations are provided.” (American Society for Bioethics and Humanities. Core Competencies for Healthcare Ethics Consultation (2nd ed.). Glenview, IL (2011)

Consultants, by definition, are not tasked with making the healthcare decision that is deliberated by those who are appropriate decision makers. Recommendations typically result from consultation requests, however. Ethics recommendations are grounded in the principles, values, or rules that are relevant to whatever is being deliberated. Arguments are provided for or against a particular decision and action that might be taken by those whose responsibility it is to decide and act.

The sorts of situations with which an HEC gains familiarity for consultation involve the beginnings and endings of life, valuational conflicts between patients/families and providers, unclarity regarding who is an appropriate surrogate decision maker, questions regarding the existence or application of relevant policies or principles, etc.

The skills required of a healthcare ethics consultant are delineated in a Core Competencies publication of the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities. These include interpersonal, communication, administration, and facilitation skills, plus those needed for discernment, assessment and evaluation of healthcare situations. ASBH has implemented a certification process for HEC that is described at https://asbh.org/certification/hcec-certification.

Tarris Rosell, PhD, DMin, HEC-C

2/15/2023

What are bioethics case studies?

Case studies are a practical means of connecting bioethical concepts with real world scenarios. Case studies typically provide information regarding the patient, the patient’s medical diagnosis, patient expectations, family dynamics and additional contextual features. These allow ethics consultants to practice with different situations, understanding their complexities, and offer novel ways of navigating forward. Case studies can be theoretical or based on real patient scenarios. The Center for Practical Bioethics publishes new case studies frequently and are found in the Case Studies category in our Resources Library.

Case studies are a practical means of connecting bioethics concepts with real world scenarios. They typically include a story about some particular healthcare situation, either actual or hypothetical. That narrative is followed either by an ethics discussion or questions for discussion.

A case narrative involving a patient-provider situation might include information about the patient, including age, gender identity, ethnicity, religious affiliation if any, their psycho-social background and family dynamics. Relevant medical diagnoses or other medical history are described, along with the patient’s values and expectations regarding treatment. The context in which the case situation arises may be described also, whether home care, outpatient or inpatient, acute care or residential facility. A description of the care team provides more context for understanding the ethics issues that make a case worthy of study.

Case studies are useful for teaching and learning, providing opportunity to do ethics reflection on healthcare situations that have arisen or might in the future.

Tarris Rosell, PhD, DMin, HEC-C

Ryan Pferdehirt, D. Bioethics, HEC-C

02/15/2023

What is an ethics committee?

Virtually all health professionals face ethical issues in their interactions with patients and families. COVID-19 brought many of these issues, particularly equity, to the forefront. A review of case studies at PracticalBioethics.org conveys how diverse and traumatic these issues can be. Responding to ethical dilemmas, family crises, moral failure and inadequate policy supports patient care, reduces risks for institutions and decreases professional burnout.

In 1992, The Joint Commission on Hospital Accreditation (currently known as TJC) began requiring every accredited hospital to have a “mechanism” to handle ethical concerns within its institution. In recent years, TJC lifted that requirement; yet the vast majority of US hospitals had subsequently implemented something like an ethics committee. Most involve a multi-disciplinary body comprised of physicians, nurses, administrators, social workers, chaplains, community volunteers and others. A smaller percentage of healthcare institutions would also have on staff or contractually (e.g., through the Center for Practical Bioethics) someone trained and available 24/7 for clinical ethics consultation. A consultant with skills of moral discernment, communication, facilitation and mediation is oftentimes able to be helpful in situations when stakeholders don’t know or can’t agree on what to do.

Ethics Committees (EC) have three primary functions:

(1) CONSULTATION – To serve as a resource for patients, families and stakeholders to resolve difficult issues that arise in patient care.

(2) EDUCATION – To provide continuing ethics education to the institution and more specialized training to EC members.

(3) POLICY – To participate in institutional policy formation and review to maintain and improve ethical treatment of patients on a systems level.

By their own admission, many EC members, especially in smaller healthcare institutions, have neither adequate ethics training nor the tools to perform this work. Within their institutions, the role of the EC may not be well defined. Lacking strong educational programs to develop future leaders, ECs flounder when key staff rotate off. According to a 2021 study (BMC Medical Ethics) by Marion Danis et al., “The greatest challenge facing HCECs is lack of resources, except in small hospitals where the greatest challenge is underutilization.”

The Center for Practical Bioethics has risen to the challenge of collaborating with EC leaders and their healthcare institutions. We provide educational and consultation resources to supplement what ethics minded colleagues in many places have or lack.

Tarris Rosell, PhD, DMin

02/09/2023

What is the Ethics Committee Consortium?

The Ethics Committee Consortium (ECC), founded by the Center in 1986, is the longest continuously operating program of its kind and a proven model for educating healthcare provider ethics committees (ECs) nationwide. As of 2023, nearly 500 individuals participate in the ECC – including acute and hospice care workers, doctors, nurses, surgeons and academics – representing more than an estimated 300 ethics committees.

The ECC provides practice-oriented bioethics education, clinical and non-clinical ethics consultation, healthcare policy review, and clinical ethics research support. We also host webinars, publish a monthly newsletter, assist ECs in developing core competencies in bioethics, and serve on members’ Institutional Review Boards (IRBs).

What clinical ethics services can CPB provide to my organization?

Unfortunately, while most hospitals report that they have an Ethics Committee, the vast majority say that it is under-resourced, under-utilized, unclear about its role, and lacks support from organization leaders. This is particularly the case for smaller and rural hospitals. Moreover, only about 5% of health professionals report having received formal clinical ethics training. Many feel unprepared for challenging situations, citing lack of access to credentialed healthcare ethics consultants and resources.

From organizations struggling to maintain a functioning ethics committee to healthcare systems operating sophisticated ethics programs, the Center will work with you to design services that meet your needs.

The Center offer two types of Ethics Services agreements: Core and Advisory.

CORE SERVICES

ETHICS COMMITTEE, EDUCATION, AND POLICY

- Ethics Committee Consortium

- Facilitated Participation in Ethics Committee Consortium and Network

- Online Discussion and Communication

- Online Resources and Policy Library

- Periodic Electronic Training Resources

- Retrospective Case Review

- Interactive Webinars and Training

- Skill Development Workshops

- Provide Educational Offerings for Staff

- Institutional Policy Development Assistance

ADVANCE CARE PLANNING & END-OF-LIFE DECISION-MAKING

- Support for organizational participation in Transportable Physician Orders for Patient Preferences TPOPP/POLST

- Caring Conversations® Advance Care Planning workshop

- Support for participation in National Healthcare Decisions Day

COMMUNITY BENEFITS

- The Center for Practical Bioethics provides an extensive array of community programming and impact, which may be viewed at practicalbioethics.org.

ADVISORY SERVICES

Advisory Services include all Core Services plus these options:

- Customized Workshops

- Inpatient Ethics Consultation

- Consultation Case Review and Recommendations

- Face-to-Face Family Meetings

- Policy Development and Integration

What educational programs and resources does CPB offer for free?

LECTURES AND SYMPOSIA – The Center offers educational programs in-person and virtually, including named lectures honoring gifted past leaders at the Center.

- Rosemary Flanigan Lecture

- Joan Berkley Symposium

- Christopher Forum

WEBINARS – The Center provides webinars on the ethical implications of current issues in health and healthcare featuring national experts. See dozens of Pandemic Resources created since the emergence of Covid-19. Subscribe to our newsletter to be notified of future webinars.

BIOETHICS LIBRARY – Our Library includes thousands of reports, guidelines, briefs, program resources, interviews, lectures, symposia and case studies, our most searched page on the website at no cost.

Why should I care about Artificial Intelligence (AI) in health and healthcare?

Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies are playing a growing role in hospitals and other healthcare settings. These systems serve as powerful diagnostic and care management tools, amplifying the abilities of the clinicians that use them. However, recent events have shown that AI systems can reproduce biases in the data used to create them, potentially deepening existing societal inequities. While AI holds great potential to improve healthcare outcomes, responsible development and thoughtful integration are necessary to ensure that these improvements will benefit everyone while also keeping them safe.

What is Advance Care Planning?

Advance care planning is a process where individuals identify, communicate, and document their healthcare preferences to ensure they receive the care they would want in situations where they cannot speak for themselves. This process involves appointing someone to communicate those preferences in the event they cannot speak for themselves. Though there are many aspects to advance care planning, chief documents used in the process the process include the Advance Directive, which helps identify a person’s healthcare preferences, and the appointment of a healthcare representative. The latter, often referred to as the Durable Power of Attorney for Healthcare (DPOAH), establishes a surrogate decision-maker (or healthcare representative) to speak on a patient’s behalf if the patient is incapacitated.

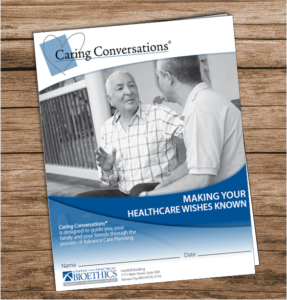

What is Caring Conversations?

Caring Conversations® promotes advance care planning and is the Center’s oldest program. For over thirty years, Caring Conversations® has helped communities document their healthcare preferences and appoint surrogate decision-makers. To achieve this, the Center hosts in-person workshops, online webinars, and provides advance care planning resources to community members all across the nation. Additionally, the Center works directly with healthcare organizations to bolster their advance care planning goals and increase patient satisfaction.

What is TPOPP?

TPOPP/POLST is a bi-state initiative of the National POLST Program. At its root, TPOPP/POLST is grounded in the belief that individuals have the right to make their own healthcare decisions and to shared decision making. The Transportable Physician Orders for Patient Preferences (TPOPP/POLST) Initiative is designed to improve quality of care for those living with serious illness and/or frailty by translating patient/resident goals and preferences into medical orders. TPOPP/POLST achieves this by establishing communication between the patient/resident or recognized decision-maker and healthcare professionals/ providers, thus ensuring informed medical decision-making. TPOPP/POLST is a bi-state initiative, headquartered at the Center, and led by advocates in Missouri and Kansas.

How can the Center help me deal with a healthcare crisis?

You can call the Center for help charting a path through a healthcare crisis on behalf of yourself or someone you care about. For example, a distraught adult daughter recently called the Center about her confused but still independent mom experiencing bouts of paranoia and anxiety caused by dementia. The daughter respected her mom’s autonomy but struggled with being accused by her mother of stealing from her. Resources in their rural community were limited. We helped the daughter develop a plan and set priorities to ensure her mom’s dignity.

Please note that the Center does not provide legal advice.

You can contact us by phone at (816) 221-1100 for help.

What is Democratic Deliberation?

Democratic Deliberation is rooted in the idea that ordinary people should have meaningful opportunities to participate in important social questions. Proponents of a deliberative democracy argue that our collective decisions will be better—more informed, more sustainable, more fair—when citizens are actively engaged in their own governance.

Over the past three decades this idea has increasingly been subject to experimentation in the form of deliberative forums that convene people with different backgrounds and perspectives to learn and talk together in a serious and substantive way about shared challenges in search of collective solutions. Deliberative forums have been used in the United States and around the globe to gather well-informed, carefully considered input on tough social and policy questions for which there is no one right answer and about which people disagree.

Evaluations of deliberative forums have shown that:

- Participants gain knowledge about the subject matter, regardless of their education level

- Participants gain understanding and appreciation of others’ situations and perspectives

- Participants may moderate their views and become more public-spirited in their orientation

- Participants gain trust of other participants

- Participants build deliberative capacity and confidence

- Deliberations can reduce partisan animosity

Links:

- Blacksher E, Diebel A, Forest PG, Goold SD, Abelson J. What Is Public Deliberation? Hastings Center Report 2012;42(2):14-17. PMID:22733324, DOI:10.1002/hast.26. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hast.26

- Blacksher E. Participatory and Deliberative Practices in Health: Meanings, Distinctions, and Implications for Health Equity. Journal of Public Deliberation 2013;9(1): Article 6. http://www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol9/iss1/art6

- Abelson J, Blacksher E, S. Boesveld, Goold SD, Li K. Public Deliberation in Health Policy and Bioethics: Mapping an Emerging, Interdisciplinary Field. Journal of Public Deliberation 2013; 9(1): Article 5. http://www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol9/iss1/art5

Erika Blacksher, PhD

03/17/2023

What is population health bioethics?

Bioethics has always been a “big tent.” From its origins to present day, bioethics has continually expanded the boundaries of its inquiry to keep pace with questions raised by developments in technology, treatments, big data, culture and social movements. In the past two decades, new subfields of bioethics have emerged that focus on questions raised by the health of populations, the environment and the planet. These subfields have arisen in the face of a resurgence in infectious diseases, surging inequality, globalization, climate change, and the revival of social justice movements around the world.

Population health bioethics raise questions that differ in important respects from ethical questions that arise in the delivery of healthcare, the doctor-patient relationship, clinical research, and genetics and genomics. Importantly, population health bioethics is oriented toward the prevention and distribution of illness and disease in groups, rather than toward responding to extant illness and disease in individuals. Whereas clinical ethics attends to the patient as person, their capacity and caregivers, and informed preferences and values, population health bioethics focuses on the social, economic, environmental and political conditions that produce and distribute health and longevity at the group level, whether defined in terms of a geographic, sociodemographic or political community.

This population-level perspective raises an array of questions that are just beginning to be studied and debated. They include, for example, questions about:

- whether health is a special good,

- the balance of social and individual responsibility for health,

- the fair or equitable distribution of health within countries and among countries,

- how to measure health and health inequalities,

- how to allocate health resources between generations in the face of an aging global population, and

- how to balance disease prevention with the protection of civil liberties, privacy and confidentiality.

This broader focus also has implications for the types of ethical frameworks and disciplines that need to be brought to bear for analysis and deliberation. Importantly, theories and frameworks need to have the scope and conceptual resources to address the roles of governance structures, social institutions, and public policies that create the conditions that shape people’s health prospects and that of the planet they inhabit. Theories of justice, human rights frameworks, and perspectives from political philosophy are often used and adapted for considerations of population health bioethics. As with bioethics generally, those who pursue questions of population health bioethics come from a variety of disciplines, such as philosophy, ethics, medicine, nursing and law. With its focus on the health of communities and populations, other disciplines and perspectives from epidemiology, demography, public health, economic development, and global health are increasingly joining the discourse and debates in population health bioethics.

RECOMMENDED RESOURCES (ordered by year of publication)

- Dan E. Beauchamp and Bonnie Steinbock, eds. New Ethics for the Public’s Health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Timothy Evans, Margaret Whitehead, Finn Diderichsen, Abbas Bhuiya, Meg Wirth. Challenging Inequities in Health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Sudhir Anand, Fabienne Peter, and Amartya Sen, eds. Public Health, Ethics, and Equity. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Paul Farmer. Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2005.

- Madison Powers and Ruth Faden. Social Justice: The Moral Foundations of Public Health and Health Policy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Yukiko Asada. Health Inequality: Morality and Measurement. Toronto, CA: University of Toronto Press, 2007.

- Angus Dawson and Marcel Vegweij, eds. Ethics, Prevention, and Public Health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Norman Daniels. Just Health. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Shlomi Segall. Health, Luck, and Justice. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010.

- Sridhar Venkatapuram. Health Justice. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2011.

- Ruth Gaare Bernheim, James F. Childress, Richard J. Bonnie, and Alan L. Melnick. Essentials of Public Health Ethics. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2015.

- Drue H. Barrett, Leonard W. Ortmann, Angus Dawson, Carla Saenz, Andreas Reis, and Gail Bolan, eds. Public Health Ethics: Cases Spanning the Globe. New York, NY: Springer International Publishing. 2016. Available online at: http://www.springer.com/us/book/9783319238463

Erika Blacksher, PhD

03/17/2023

How is the Center funded?

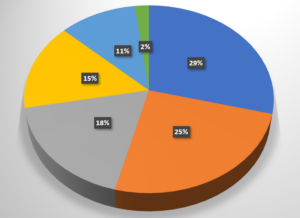

In 2021, the Center derived funding from six sources:

Donations (29%)

Earned Income (25%)

Special Funds/Endowed Chairs (18%)

Special Events (15%)

Program Grants (11%)

Honoraria and Miscellaneous (2%)

How can I support the Center’s work?

Our Programs

Make an impact

Every dollar you give helps providers, clinicians, patients and families decide what to do when it’s hard to agree about the “right” thing to do.